Family Focus Adoption Guide Program

THIS PROGRAM IS ON HIATUS WHILE WE EVALUATE IF NATIONWIDE PLACEMENTS WILL CONTINUE

If you have reached this page in error, please click

HERE to return to our home page.

Introduction

Sending children long distances away from home to be adopted by people they have barely met in the one, two, or, if very lucky, three pre-placement visits that are the usual practice across the country, is insufficiently supportive, let alone protective, of these older-than-toddler children. Expecting that the usual once a month supervision (even with extra visits as needed) by a local caseworker, who is too often overwhelmed by his/her local caseload, is going to give sufficient support post placement for the child is wishful thinking. By and large, the children in need of placement over such long distances are the children who have already been multiply rejected: aside from their birth families, there has been, at least, one foster home - their current one - that is not keeping them. Often, there have been more. Even if all goes well, the process itself can be overwhelming for these children, especially in the first months.

Some sort of model had to be developed for these children and their new families. No matter how high the much-ballyhooed success rate of these placements is by all the agencies that match children and far away families, there are always children for whom it is not successful. Some of those might have worked with more support for the child. But even when it doesn't work the child must be protected from feeling - or worse, being - blamed for the failure of the placement, even by his/her own self. And the child must always be protected from the relatively few people who get through all our agencies' screening processes who will hurt kids.

The Philosophy

All adoptions, and therefore, all disruptions, are always and only the result of adult decisions, and thus, no child can ever be responsible for the failure of his or her own placement, no matter what the child's behavior. Our practice must always reflect that truth.

Disruptions often occur because the adults get overwhelmed. Many, if not all, of those times, the adults get overwhelmed because the children were overwhelmed first. For that reason, aside from the simple humanitarian one, the goal must be to keep the children from being overwhelmed.

Easier said than done. When older children are placed into adoption, they either deal with their feelings about their abandonment histories prior to the finalization or they most assuredly will be dealing with them post-finalization. It is in everyone's best interest to have that work done earlier rather than later. But the feelings can be overwhelming. Adoptive parents, by their very role, cannot often help the kids with this work as the child's relationship with them is part of the feelings (loyalty) that they are struggling with.

It has been FAMILY FOCUS ADOPTION SERVICES' great insight, since our opening in 1987, that much of this work is best done by the children themselves, and will be done, often unconsciously, if they are given an umbrella of adult protection under which they can do it, at their own pace, and to their own level of satisfaction. We trust the kids and we trust that they - internally - know best what they need. It is our job to provide them the support, protection and control that they need in order to do their adoption work. To a large degree those three overlap, but it is worth exploring each one alone.

The Support

The Adoption Guide program is an ingeniously simple confidence building process. A trained and well-supervised adult (Guide) is assigned to each child, through the agency, to guide the child through the adoption process, from placement through their decision about adoption. Using a graduated visiting schedule, from twice a week to once every three weeks, and taking the child through a series of adoption levels that are marked by six cards collected by the child over five months, children can become more and more certain that being adopted by the particular family they are with is the right decision for them.

The Guide meets the child when the child comes to visit the family for the first time. (If that's not possible then the Guide visits within days of the placement.) The Guide reinforces what the child should have been told already: that though this is his/her adoptive placement, the adoption can't take place yet. The child has to live with the family for a certain period of months and get to know them to make sure that this is the right family for them. So it's a 'not yet' family, and the child should not be calling the adoptive parents 'Mom' and 'Dad' yet. (We use first names).

The Guide gives the child her phone number and enough information about the program to give the child confidence in making this long-distance move. The Guide explains to the child that they are there only for the child and will never be talking to the 'not yet family' on the guide visits, other than simple politeness: 'hello,' 'goodbye' and making the next appointment. Children are also told that although the Guide will be there for their first visit within three days of the child moving in, the child can ask for a visit anytime earlier, if necessary.

The Protection

Aside from having a Guide, the Guide's phone number, and knowing the Guide works solely for the child, there is one very specific protection the Guide gives to each child: a Stop Card.

It is the first card given to the child by the guide at their very first meeting, usually while the child is visiting. It is a red card, and on the front it simply says, 'STOP!' On the back, it reads, 'Emergency Stop The Process Card.' On the back of this card is also where the name of the Guide and the Guide's phone number is recorded. This card, which the child can take back home with them or leave in the 'not-yet' home after the visit, is the child's protection card. It requires nothing more of them to stop the whole process than to give it to their Guide at any time - once they've moved - or their social worker, foster parent, or other trusted adult prior to their move. It means trouble - even if the trouble can't be identified or named by the child. It requires the adults to intervene until that child is comfortable enough to take the card back. Children given such power do not misuse it foolishly or carelessly. They know that they would be risking their adoptive placements by misusing the card, and they do not often, if ever, choose to do that. They will hold onto their card unless they have good reason to hand it to the Guide. The program belief behind the card is always: better safe than sorry.

The red Stop Card serves to balance out the power imbalance that is a necessary part of all adult-child relationships. In the same way that all backup systems allow folks to be braver, it allows the child to invest in his not-yet family, while having a way to escape from the family should he discover a need to do so. It also conveys to the child the Guide's profound respect for them and their right not only to be safe, but to feel safe.

The Control

The series of cards that the child is given to mark each level also mark the control that the child has over the process. In order to be adopted, the child must collect - and hand in at the end - all six cards, including the Stop card. Since the child moves through each level only by their own assent, the child is in total control of not only when, but also whether, they get adopted by their not-yet family.

It is allowing the child this control that makes their adoptions solid when they do occur. Rather than adoption being something that is done to the child, or something the child has gone along with, it becomes something that the child has chosen for him/her self with full knowledge and experience of the adoptive family.

Although the child is guided through his/her levels, no child ever has to proceed from one level to the next. Children are always given the Guide's opinion - 'I think you are ready' - but move only if they themselves say that they are ready to do so. However, when it comes near the end of the process - at least seventeen weeks into it - it is the child who must tell the Guide that he/she is ready for final work that he/she must do.

That work is for the child to ask each not-yet parent, individually and separately, if the parent is willing to become the child's forever parent. This strong confidence building step of taking responsibility for their own adoptions is what gives the children the certainty that they are in control of the process. It also gives them the surety that they have not been crippled by all the earlier rejections and abandonments by other adults.

The Process

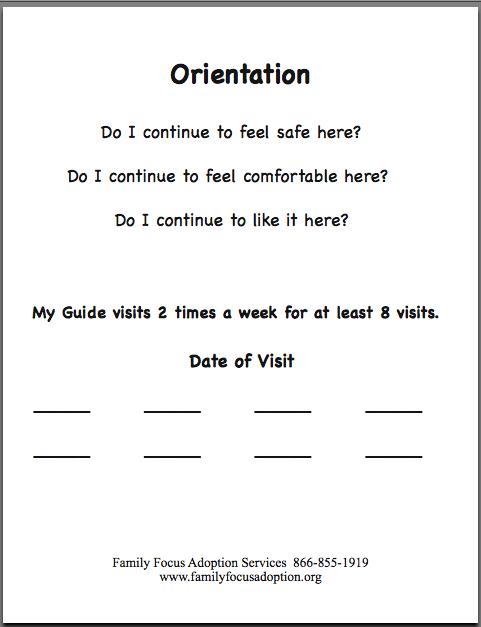

Once the child moves in - because they made the decision to do so, after they have gone back home following their trip to the not-yet family - the Guide will visit within days. On the Guide's very first visit, she will give the child the second card, the Orientation Card. This card has, on its reverse side, the three questions that the children are to be thinking about during this orientation time: Do I continue to feel safe here? Do I continue to feel comfortable here? Do I continue to like it here? The guide will come twice a week for at least four weeks. Other than simple politeness, and making the next appointment, the Guide does not speak with the not-yet family. She is not the family worker and she belongs solely to the child as a guide. This is crucial for the child to trust the Guide. The Guide and child will undoubtedly talk about all the differences between the old home and the new one. Perhaps they will play games together, or go for a walk together. The agenda is determined by the child always. Guides are neither the caseworkers nor the therapists.

At the end of that first month, the Guide can offer to the child the option to begin their Adoption Levels if three conditions have been met: The child has to be in her regular program (usually school) at least two weeks; the child has to have had at least eight Guide visits; and the child has to affirm that they want to begin their adoption work. The Guide will only be coming once a week on Level One, and the child has to understand that, too.

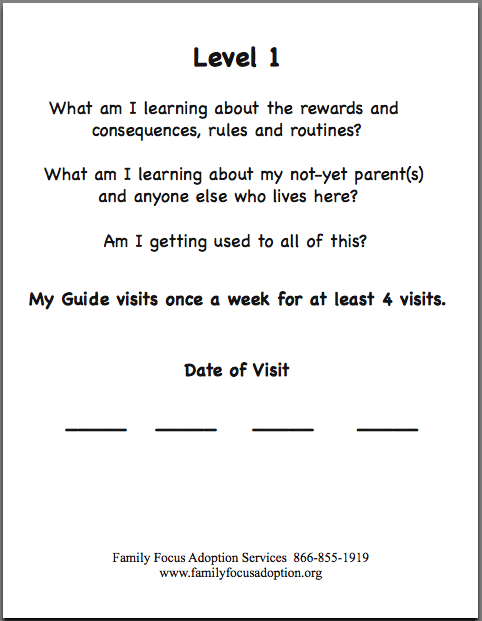

In order to make it official, the guide gives the child the Level One Card, the third of the six cards the child will collect. The work on Level One through Level Four is the adoption work. It begins very slowly by talking about adoption and moves up to the child making the decision about being adopted by this particular family. The child must be on Level One for at least four visits. The work of this level - and it is written on the back of the card - is for the child to get to know the family, the other members of the household, the rules, routines, rewards, and consequences. At the end of the month, after seeing the child twelve times in eight weeks, if the Guide is satisfied that the child has done all that work, the child becomes eligible for Level Two.

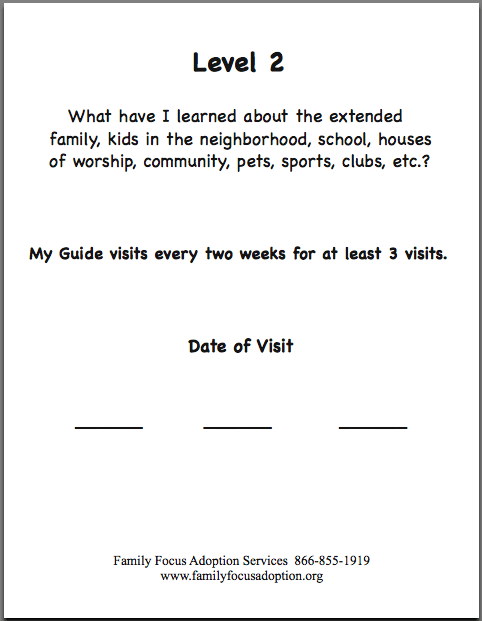

Level Two means the Guide comes every two weeks, but there will be at least three visits, so the level lasts for six weeks. The child is given their Level Two Card. The work of this level, again written on the back of the card, is for the child to get to know the extended family, the school, the neighborhood kids. The child needs to learn about their house of worship if there is one; about the pets if there are any; about sports teams or rec clubs that they might belong to.

Again, at the end of the three visits, the child becomes eligible to move to Level Three, where the Guide visits every three weeks, and usually twice. Level Three has two parts. Level 3A, if the child is deemed ready for it, and agrees that he or she is ready, is the adoption practice step. The child is given their fifth card, the Level 3 Card, and is told to practice being adopted over the next three weeks. It is the 'practice step for getting out of foster care.' The child is asked to focus on whether or not he has learned all he needs to know about his not-yet family in order for him to choose them as his adoptive family. The child is also told that this is as far as the guide can take the child through the process. Levels 3B and 4 will have to be the child taking the Guide.

After the first three-week practice, if the child is certain that they are ready to proceed, the Guide tells them what they have to do on Level 3B. The child is told that he or she will have to ask each not-yet parent if that not-yet parent is willing to become his forever parent. It is a question that can't be asked while the Guide is there and it must be asked privately. Each parent must also be asked separately. The Guide sets up another appointment for three weeks later, but that is subject to being cancelled for an earlier appointment if the child calls and affirms that he has asked, and that the not-yet parents have said yes. The Guide would also have to confirm that with the family's caseworker.

At that 3B meeting with the child, the child is given the sixth and final card - the Level 4 Card - and permission to begin calling the not-yet parents 'Mom' and 'Dad.' While not yet required, it is suggested to the child that he or she practice it because at the Covenant Ceremony, it will be required. The child is then told about how the Covenant Ceremony works and given the date for it, if known. A week before that Ceremony, the Guide comes back for an almost final visit, during which time the Guide explains in great detail how the Covenant Ceremony will go, and what happens afterwards until finalization.

Counting the visiting meeting, a minimum of nineteen face to face contacts have occurred, and the child will have lived with the family approximately five months. The final visit will be the Ceremony.

The Family Part

Parallel to the Guide's work with the child will be the Caseworker's work with the family. As the child moves from level to level, so too will the family. Aside from the once a month supervisory visit, the Caseworker will also be taking regular calls from the family. During orientation, the family - either parent - will call the Caseworker every Monday and every Friday to report on what is going on in the house. At Level One, the calls will go to once a week; at Level Two, they will go to every other week, at Level Three, to every three weeks. Once the Covenant Ceremony has arrived, the contact will consist of the once a month supervisory visits until finalization.

Communication

On top of all the normally required reports, email reports are the main form of communications. Every visit of the Guide, and every call from the family or visit to them, will be documented in an email and sent to the sending state's Caseworker by the respective supervisors on the case. Guides and Caseworkers are to see each other's notes, and they must talk at least once a month, prior to the Caseworker visit to the family. The more talking they do with each other, however, the better. CASA workers, therapists etc. can be included in the email notes, but that is determined on a case-by-case basis.

The Covenant Ceremony

The Covenant Ceremony marks the discrete moment in time when a 'not-yet' family becomes a 'forever' family. It is a ceremony in which the 'not-yet' parents each sign separate Adoption Covenants, promising to be their child's parents forever and unconditionally. In response, the child then signs his own conditional Covenant, accepting the parents' commitment and making his own to being a forever family member, on the one and only condition that the parents have spoken the truth. He opens with his current name, but signs with his adopted name.

The Ceremony can be as big or as small as the family likes. Caseworkers from the sending jurisdictions must be invited and, if they can't come, they should be invited to join by speaker phone. The Guide, and the supervising Caseworker must be there. A third agency person to serve as master-of-ceremonies always makes things easier, but generally makes no sense if neither the child nor family know the person.

All Covenants are to be witnessed by the supervising caseworker, and at least one other person. Each party and each witness signs six original Covenants. At the end of the ceremony, one complete set goes to each parent; one goes to the child; one is sent to the sending jurisdiction; one is kept by the supervising Caseworker; and the last goes into the child's file to be sent to the finalization judge.

When the last Covenant is witnessed by the last witness, the child is declared adopted (but understood that finalization is yet to come). The Guide's work is done.